Composition is the invisible architecture that gives your photographs strength, meaning, and visual impact. While technical aspects like exposure and focus are crucial, it's composition that separates snapshots from art. Understanding compositional principles allows you to create images that guide the viewer's eye, evoke emotion, and communicate your vision effectively.

In this guide, we'll explore powerful compositional techniques that go beyond the basic rule of thirds, giving you a comprehensive toolkit to strengthen your photographic vision.

The Foundation: Rule of Thirds

Let's start with the most familiar compositional guideline. The rule of thirds divides your frame into a 3×3 grid, suggesting that placing subjects along these lines or at their intersections creates more balanced, interesting compositions than centering everything.

While this rule provides an excellent starting point, its true value comes from understanding why it works—it creates asymmetrical balance and visual tension that engages the viewer more than centered compositions.

Pro tip: Don't just place your subject at an intersection without thought. Consider which intersection creates the most pleasing relationship between your subject and other elements in the frame.

Leading Lines: Guiding the Eye

Leading lines are one of the most powerful compositional tools available to photographers. These are lines within your image—whether literal (roads, fences, rivers) or implied—that direct the viewer's attention through the frame, typically toward your main subject.

Types of Leading Lines:

- Straight lines create direct, forceful pathways (highways, piers, railroad tracks)

- Curved lines create a more gentle, flowing journey (winding paths, S-curves in rivers)

- Converging lines (like a road disappearing into the distance) create depth and perspective

- Implied lines can be created by a sequence of objects or even by a person's gaze

When using leading lines, consider where they enter the frame and where they lead. The most effective lines enter from the corners or edges and guide the eye toward your subject or through important elements of your composition.

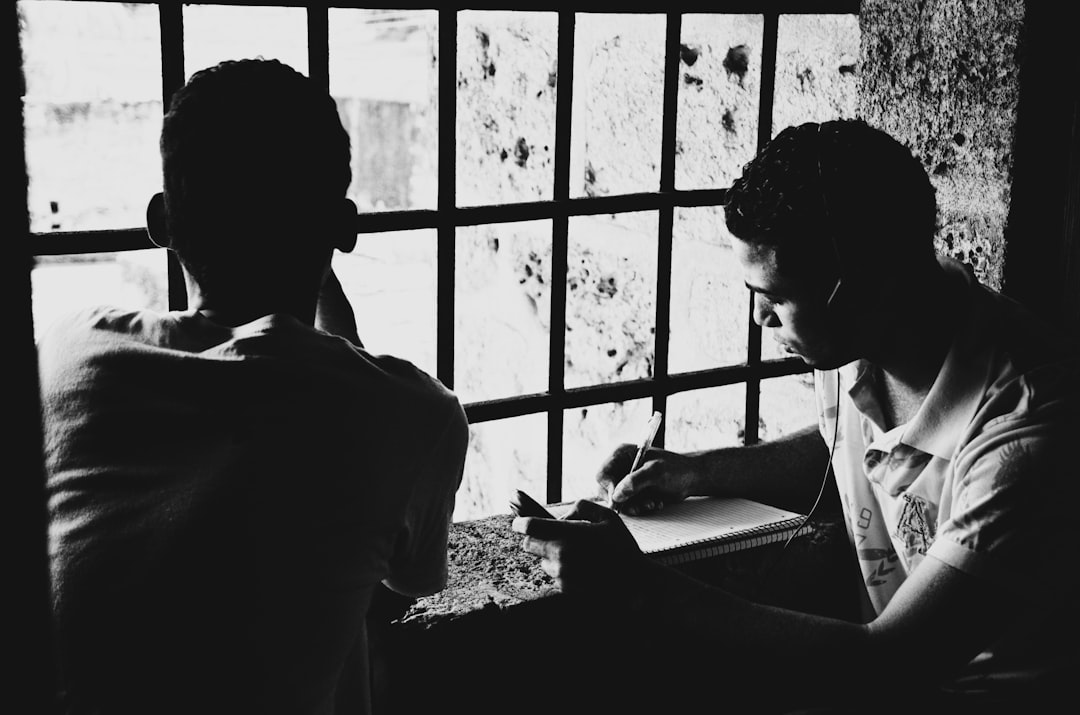

Framing: Context and Focus

Natural frames within your scene can add depth, context, and focus to your images. Framing involves using elements within your environment to create a "frame within a frame" that surrounds your main subject.

Common Framing Elements:

- Archways, doorways, and windows

- Tree branches or foliage

- Rock formations or cave openings

- Urban structures like bridges or buildings

Effective framing does more than just surround your subject—it provides context, adds depth by creating foreground interest, and can help isolate your subject from distracting backgrounds.

For maximum impact, consider exposing for your subject and allowing the framing elements to fall into shadow, creating a more dramatic, focused effect.

Symmetry and Reflections: Perfect Balance

While the rule of thirds encourages asymmetry, sometimes perfect symmetry creates powerful, striking compositions. Symmetrical compositions convey a sense of harmony, formality, and order that can be visually compelling.

Types of Symmetry:

- Bilateral symmetry (reflection across a vertical or horizontal axis)

- Radial symmetry (elements arranged around a central point)

- Approximate symmetry (nearly but not perfectly symmetrical)

Water reflections are particularly effective for creating symmetrical compositions in landscape photography. In architecture photography, building facades and interiors often present excellent opportunities for symmetry.

Pro tip: While pursuing symmetry, look for a single asymmetrical element to create a "broken symmetry" that adds interest and focal point to your composition.

Patterns and Repetition: Order and Disruption

The human brain is naturally drawn to patterns and repetition. Incorporating these elements into your photography creates visually satisfying compositions that immediately engage the viewer.

Patterns can be found everywhere in both natural and man-made environments:

- Architectural elements like windows, bricks, or tiles

- Natural patterns in leaves, flowers, or animal markings

- Repeated objects like bicycles in a rack or chairs in a row

A particularly powerful technique is to find a pattern and then capture its disruption—the single red flower in a field of white, the one person walking in the opposite direction, or the broken tile in an otherwise perfect floor. This "pattern break" creates a strong focal point and tells a more interesting visual story.

Negative Space: The Power of Simplicity

Negative space is the empty area surrounding your subject. Far from being "wasted" space, these empty areas can dramatically strengthen your composition by:

- Creating breathing room that allows your subject to stand out

- Conveying emotions like isolation, peace, or contemplation

- Providing balance to visually complex subjects

- Allowing the viewer's eye to rest and then return to the subject

Minimalist compositions with significant negative space often create the most impactful, memorable images. When using negative space, pay particular attention to the shapes formed by this space—they should complement your subject rather than distract from it.

Depth and Layering: The Third Dimension

Photography compresses three-dimensional scenes into two-dimensional images. Effectively conveying depth creates more immersive, dynamic compositions.

Techniques for Creating Depth:

- Foreground, middle ground, background: Include elements at different distances

- Overlapping planes: Allow elements to partially block others to indicate spatial relationships

- Atmospheric perspective: Capture how distant objects appear less contrasty and more blue

- Selective focus: Use shallow depth of field to separate subjects from backgrounds

When composing layered images, ensure each layer adds something meaningful to the composition rather than creating clutter. The foreground often provides context or frames the scene, while the middle ground typically contains your main subject.

Visual Weight and Balance: The Invisible Scales

Every element in your frame has "visual weight"—the degree to which it attracts the viewer's attention. This weight is determined by factors like:

- Size (larger elements have more weight)

- Color (bright, saturated colors are "heavier")

- Contrast (high-contrast areas draw more attention)

- Complexity (detailed areas appear weightier than simple ones)

- Position (elements closer to the center often have more weight)

A balanced composition distributes visual weight effectively across the frame. This doesn't mean symmetrical placement—a small, bright object near the edge can balance a larger, darker object closer to the center.

Understanding visual weight allows you to create dynamic tension or harmony depending on your creative intent.

The Golden Ratio: Nature's Composition

The golden ratio (approximately 1:1.618) appears throughout nature and has been used in art and architecture for centuries. In photography, it manifests in several ways:

The Phi Grid

Similar to the rule of thirds but with the lines placed according to the golden ratio, creating a slightly different set of power points.

The Golden Spiral

A logarithmic spiral based on the golden ratio that can guide placement of elements and the flow of your composition. Many naturally occurring spirals (shells, flower patterns) follow this ratio.

While more complex than the rule of thirds, compositions that incorporate the golden ratio often have a naturally pleasing, harmonious quality that resonates with viewers on a subconscious level.

Breaking the Rules: Intentional Composition

The most important thing to remember about compositional "rules" is that they're merely guidelines, not strict requirements. Great photographers understand these principles deeply—and know exactly when and why to break them.

Centered compositions, intentionally tilted horizons, or deliberately unbalanced frames can create powerful images when done with purpose. The key is intentionality—breaking rules randomly creates chaos, but breaking them purposefully creates art.

As you develop your photographic eye, you'll begin to intuitively sense when to follow compositional guidelines and when to diverge from them to express your unique vision.

Practice Makes Permanent

Improving your compositional skills requires deliberate practice:

- Study the work of master photographers and analyze their compositional choices

- Practice "compositional exercises" where you photograph the same subject using different principles

- Review your images critically, asking what compositional changes might strengthen them

- Consider how composition supports the emotional or narrative intent of your image

Over time, these principles will become second nature, allowing you to compose intuitively while shooting rather than consciously thinking through each rule.

What compositional techniques have transformed your photography? Share your experiences or questions in the comments below!